The Future of Software Documentation in the Age of AI

HeavybitHeavybit

HeavybitHeavybit

As AI becomes more of a reality in software development, teams are experimenting with a variety of use cases, including documentation and technical writing. In this article, veteran technical writer (and co-author of Docs for Developers: An Engineer’s Field Guide to Technical Writing) Heidi Waterhouse discusses some of the biggest mistakes teams make using AI for docs, as well as the best opportunities to use AI productively to support user journeys.

More Articles on How Documentation and Software Dev Are Evolving:

- Article: Who Owns the Documentation and Why It Should Be the Robots

- Podcast: Documentation Deep Dive with Megan Sullivan of Gatsby

- Video: Building Great API Docs

- Video: How Great Documentation Drives Developer Adoption

AI as an Assistant, not a Solution

Waterhouse elaborates on her recent session from the LeadDev conference, at which she spoke on a similar topic. “The focus of my talk was discussing things we know AI can do well, and how to make that fit with our understanding of what people need from documentation.”

The author suggests that the key to getting value out of large language models (LLMs) today is thinking about AI “as an assistant, and not a solution. Because thinking about it as a solution is what leads us down some unfortunate paths that are really hard to dig ourselves out of.”

Heidi Waterhouse discusses AI in documentation at LeadDev. Image courtesy LeadDev.

Are LLMs the Best Tool for Software Docs and Technical Writing?

Freshness: Using RAG to Ensure Docs Stay Up-to-Date Instead

Aside from hiring a good writer a year or so before launching a product to document it properly, Waterhouse suggests that product teams identify what can and can’t be easily documented, such as standardized OpenAPI documentation. “There's not a lot of distinction between writing a good test case and writing a good prompt. The things you do to test are the things that you need to document: How do I do this thing? And so we go into test cases and extract user stories from those, because we know that those work.”

The author points out that alternatives like retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) may be better suited to maintain docs freshness than using a LLM as a catch-all solution, even if it was trained on a large dataset. “Although we get better answers from very large [data] corpuses, I think it is dangerous because for nearly every LLM out there...their training corpus is at least a year old, and we don’t know exactly what it contains.”

“So if you have made software [changes] in that time, the LLM doesn't know about it and it's not retrieving fresh data. So I think you should have a small, specific, internal [focus to] look at all this stuff and use that as your context window, instead of a giant context window. That makes it both cheaper to run and more relevant.”

Indexing and Librarians: Better Docs Through Better Organization of Info?

The author notes that for documentation, the real use case that most users want isn’t longer, prettier notes to read, but the ability to ask a specific question in natural language and receive a contextually correct, helpful answer. “That's the ‘killer app.’ That requires some indexing. I haven't built this yet myself, because nobody has paid me to do it. But being able to ask any question and get an authentic answer: That’s what you want.”

To get to such a state requires proper indexing of product information, so that your system can return a specific, accurate response. In other words, a highly deterministic result that’s at odds with GenAI’s inherently non-deterministic nature. “For example, if a person asks about installation, here's the set of documents they want, and you’d refine it with the set of documents you’d return. So you’d need a natural-language sorting on pre-indexed stuff.”

“But that means that you have to pay someone to do the indexing with computer assistance. Indexing a whole set of things is difficult, but you can't just leave it to machines because machines don't understand anything. They do not ‘understand’ as they are not capable of ‘understanding’ as a concept. So I think that there's going to be an uptick in the need for librarians: People who understand semantic information and semantic relationships.”

The State of Docs vs. What Has Been Lost to Time

The author points out that the status quo of documentation isn’t reams of static docs that someone wrote years ago and no one has looked at since. “It hasn’t been like that for 15 years! But one of the interesting problems is that we've democratized technical writing and made it all markdown files, which means we've taken the expertise out of it.”

“I think back to the priesthood of Framemaker, RoboHelp, and other things we used to have. Extremely specific, context-sensitive help, where every page you were on in an application had an identifier, and if you clicked the little ‘help’ button, you would get help specific to that page. It would know where you were. There's no reason we can't have that with web applications. But nobody has been doing it. And I think just returning to something like that would be immensely useful.”

“Today, what we're writing is: Here's how to get started with what you're doing. Here's the reference documentation. There's a whole framework about what a reference doc is and what an instruction doc is and what an example doc is. And all that knowledge is difficult to transmit to founders because it's expertise. It's like asking someone: ‘Please be an expert in user interfaces.’

A Gentle Reminder: Docs Aren’t for Happy People

“I think that what we need to be doing is not just writing more documentation, which doesn't actually help people. I think what we need to be doing is making it easier to find answers to a problem that you're having. This is always the goal of documentation. Because I always say that anyone reading documentation is already pissed off.”

The author clarifies that people reading documentation don’t want to read documentation. They want to already be completing their tasks. “We need to do as much as we can so people don't have to read documentation. What if machines could read documentation and answer questions. That'd be great! But we need to design better software.”

In an ideal world, with better software, users wouldn’t need to fight a 20-page config guide to get it to work. “I tell my clients: ‘Have you made a Docker container for [your product]? Could you just give people a runtime environment that works for them so that they don't have to configure it?’”

“I think we're moving in that direction a lot for the things that we used to use documentation for. But in order to do that, you still have to know how things work.”

What we need to be doing is making it easier to find answers to a problem that you're having. Anyone reading documentation is already pissed off.

Are Smaller Models the Key to Better Docs?

Waterhouse notes that while GenAI is exhibiting potential for summarization use cases, and might be theoretically useful to gobble up reams of documentation and spit out answers, the solution isn’t quite that simple. “The thing that gobbles up data also has its own biases. It doesn't have a good semantic understanding of exactly what you're doing.”

The author suggests that an alternative might be smaller, lighter-weight models and retrieval tools trained on a highly-specific, frequently-updated dataset from which it answers questions. “But it's much clearer to think of it as a chat-based interface for an index rather than thinking of it as an answer machine.”

Weaponizing Skepticism

The author notes the problem of software documentation seeming to have all the answers...put into the hands of LLMs that still confidently give wrong answers. “Recently, there was a thread online where someone recommended feeding some Perl string into an LLM to ‘see what it parses as.’ It turns out the string parsed as a UNIX command to wipe your hard drive.”

“Now, that was obfuscated. And a human who has been on the Internet for a while knows not to run random unchecked strings. But [AI] doesn’t know that. It doesn't have any sense of danger. And I honestly think that we are going to have to code in a sense of danger. For example, how a prominent startup founder’s vibe-coding tool accidentally wiped their production database.”

“I think what we need to build into our tools is a sense of skepticism. (We can call it ‘testing,’ but testing is just weaponized skepticism.) We need to teach AI tools a sense of danger and a sense of skepticism before we let them loose in production.”

“Separately, we need to think about how AI will consume what we write in a different way than a human being might. How do we design documentation not just to be consumed by humans, but to be consumed by machine learning [algorithms]?” the author muses. “Honestly, the OpenAPI project seems like the start of that: This is a semantically sound, well-formatted thing that you can consume whether or not you're a machine. It’s predictable and you can count on it to have the same structure so that it's not going to give you weird answers.”

“Making our documentation accessible to machines is going to be valuable, because then we can use machines to ask [the documentation itself] questions.

Making Builders Future-Proof in an AI Future

Waterhouse also considers the impact of AI on engineering teams, including for junior developers. “Every time we make an advance in technology, we feel like we're going to lose those skills, and it turns out that somebody cares about preserving them. Also, even mechanization doesn't reduce the amount of work that needs to happen.”

The author cites More Work for Mother by Ruth Schwartz Cowan, a book about how laundry used to be an infrequent, time-consuming chore that required hiring washerwomen servants. After the advent of the washing machine, the position of washerwoman vanished from society, but because washing machines made doing laundry more accessible, families would do laundry more frequently, causing housewives to eventually invest the same number of hours per year doing laundry as they did previously.

“We're going to have junior testers who can run exponentially more tests, but somebody still has to write them. Those skills will be sustained, but they're not going to be ‘a whole job.’ The problem is somebody has to understand the fundamentals.”

“We watched this happen with the abstraction of languages up the stack. There are not a lot of people coding in C anymore because our abstraction layer above C is good enough. But there's a reason people are still using COBOL. It's because everything but COBOL has floating point errors for extreme edge cases of math that actually matter quite a lot. So we still need to have at least a few experts from somewhere who care about the deep internals.”

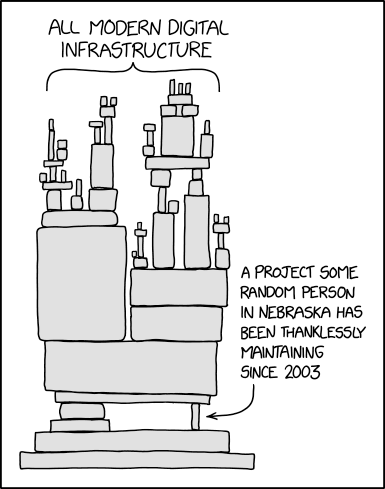

The author notes that older programming experts are retiring, leaving a vacuum for experts on computing fundamentals. “For a lot of these really sophisticated abstractions that LLMs rely on, we need someone who understands how to program the thing that programs the thing that makes the chips.” The current state of play in AI is marked by inflated expectations and budgets, but hopefully, market forces will iron out the issues.

Without experts in the fundamentals, software will have increasingly precarious dependencies. Image courtesy XKCD.

What Will Never Change: Who and What Docs Are For

The author cites Making Users Awesome by Kathy Sierra’s fundamental point about software: No one uses it because they ‘love using software.’ “People use software because they’re trying to accomplish a task or get something done.”

“And when we're writing documentation, every piece of documentation that somebody has to read slows them down on the way to getting something done. It may speed them up in the long run, they may understand something better, but on the whole we are diverting them from their task.”

Content from the Library

Generationship Ep. #38, Wayfinder with Heidi Waterhouse

In episode 38 of Generationship, Rachel Chalmers sits down with Heidi Waterhouse, co-author of "Progressive Delivery." They...

Jamstack Radio Ep. #145, The Future of Collaborative Docs with Cara Marin of Stashpad

In episode 145 of Jamstack Radio, Brian speaks with Cara Marin of Stashpad about collaborative documents. Together they explore...

Jamstack Radio Ep. #134, Commercializing Open Source with Victoria Melnikova of Evil Martians

In episode 134 of Jamstack Radio, Brian speaks with Victoria Melnikova of Evil Martians. They discuss commercializing open source...